As the number of foreign patent applications entering China increases, more and more office actions are being received by foreign applicants. When faced with these office actions, foreign applicants often find it hard to determine what the examiner’s real intention is or, even when that is clear, to know how to respond to the examiner. That is probably because: the Chinese Patent Law and its Implementing Regulations are rather concise—even the SIPO’s

Guidelines for Patent Examination (hereinafter short for “

Guidelines”) do not explain the law and its regulations in sufficient detail; the Chinese language is not easy for foreigners to understand; and the examiner sometimes does not express himself clearly.

The author summarizes below the clauses which the SIPO examiners frequently use when objecting to patent applications in the field of electronics and provides advice on how to respond to those objections.

Rule 53 of the Implementing Regulations of the Chinese Patent Law, in accordance with which a patent application is rejected, enumerates these rejection clauses: Article 22 of the Chinese Patent Law (which requires an invention or utility model to provide a technical solution in order to be patentable), Article 5 (which excludes invention-creations contrary to Chinese law or public morality), Article 9 (which stipulates that only one patent right shall be granted for the one and the same invention-creation), Article 20, paragraph 1 (secrecy examination before filing abroad), Article 22 (novelty, inventive step and practical applicability requirements), Article 25 (subject matters not eligible to be patented), Article 26, paragraph 3 (requirement for sufficient disclosure of the invention in the description), Article 26, paragraph 4 (which requires that the claims be supported by the description and define the scope of protection in a clear and concise manner), Article 26, paragraph 5 (genetic resources), Article 31, paragraph 1 (unity), Article 33 (which stipulates that amendments not extend beyond the scope of the original disclosure), Rule 20, paragraph 2 (which requires that an independent claim include all the essential technical features necessary for the solution of its technical problem) and Rule 43, paragraph 1 (which stipulates that a divisional application not extend beyond the scope of the disclosure in the parent application). (Note that the Chinese Patent Law referred to above is that which entered into force on October 1, 2009, the Implementing Regulations of the Chinese Patent Law referred to are those that entered into force on February 1, 2010, and the

Guidelines referred to are those that entered into force on February 1, 2010.)

China’s novelty requirement is almost identical to that of other countries, so the following discussion will focus on Articles 22.3, 26.3, 26.4, 31.1 and 33 as well as Rules 20.2 and 43.1, which have unique characteristics and are apt to be breached by applications in the field of electronics. An additional introduction is given to applications concerning computer programs to help the reader to understand the special way that the SIPO treats them.

As an old Chinese saying goes, “Know the enemy and know yourself, and you can fight a hundred battles with no danger of defeat.” Thus, before elaborating on those clauses the author will first touch on some aspects of the SIPO’s in-house management so that the reader can understand the examiner’s motives behind the issuance of an office action.

Part I. Procedural Economy and Quality Control

The SIPO evaluates the effectiveness and efficiency of its examiners’ work on the basis of the number of concluded applications (including both rejected and granted applications). Thus, for the purposes of procedural economy and to accelerate examination, a SIPO examiner will reject an application as long as the conditions giving rise to a rejection are fulfilled (e.g. when the applicant does not amend the application document but submit mere arguments in response to an office action). That is precisely the reason why we usually receive a

Decision of Rejection if we respond to the first office action by merely arguing with the examiner.

A quality control department has been established within the SIPO, and it is responsible for checking whether there are any flaws in the communications issued by its examiners. If the department finds any defect in an application which the examiner has failed to point out in the office action, then the examiner will get a negative appraisal. For that reason, the SIPO examiners are becoming stricter.

In recent years, the quality control department has been paying more attention to whether amendments go beyond the scope of the original disclosure. As a consequence, SIPO examiners are extremely stringent in testing whether an amendment goes beyond the scope of the original disclosure.

Part II. Details of Clauses

I. Article 22.3 (inventive step requirement)

The inventive step requirement of China is also similar to that of other countries. When the SIPO examiner considers that a claim does not satisfy the inventive step requirement, he usually points out that the technical solution defined by the claim is not inventive when compared to the combination of several solutions from a single reference or the combination of several references or the combination of a reference and common knowledge.

(1) Lack of inventive step on the grounds of the combination of several solutions from a single reference or the combination of several references

① Relevant stipulation

It is stipulated in

part II of the Guidelines, especially chapter 4 section 3.2.1.1, that “Under the following circumstances, it is usually thought there exists such a technical motivation in the prior art … (ii) The said distinguishing feature is a technical means related to closest prior art, such as a technical means disclosed in other part of the same reference document, the function of which in the other part is the same as the function of the distinguishing feature in the claimed invention in solving the redetermined technical problem … (iii) The said distinguishing feature is a relevant technical means disclosed in another reference document, the function of which in that reference document is the same as the function of the distinguishing feature in the claimed invention for solving the redetermined technical problem.”

② Typical wording in an office action

Reference 1 discloses XXXXXX. Claim X is distinguished from reference 1 by the technical feature XXXXXX. However, the distinguishing technical feature is disclosed in paragraph XX of reference 2, and it plays the same role, i.e. XXX, in reference 2 as it does in the present invention. Therefore, claim X does not possess inventive step over the combination of References 1 and 2.

③ Suggested approach to be used in a response

As can be seen from the above stipulation, it is only when several solutions from one reference or when several references together disclose the technical solution provided by a claim, and when the distinguishing technical feature of the claim over the most related prior art (i.e. cited reference 1) is known from, and plays the same role in, another solution of reference 1 (or in another reference) as it does in the claimed invention that the claim can be considered to possess no inventive step over the combination of the several solutions or the combination of several references.

The same measure can be taken to rebut the examiner irrespective of whether he combines several solutions from one reference or several references. To explain in a simple way, take the combination of references 1 and 2 for instance.

Step 1

Step 1: Is the examiner correct in holding that references 1 and 2 jointly disclose all the technical features of claim X?

Step 2: Does the distinguishing technical feature of claim X from reference 1 play the same role in reference 2 as it does in the claimed invention?

Step 3: (i) Is there any technical obstacle to be overcome in order to apply the distinguishing technical feature, disclosed by reference 2, to reference 1? (ii) Is the teaching of reference 2 away from the claimed invention?

(2) Lack of inventive step on the grounds of the combination of references and common knowledge

① Relevant stipulation

As stipulated in

the same part of the Guidelines, “Under the following circumstances, it is usually thought there exists such a technical motivation in the prior art: (i) The said distinguishing feature is common knowledge, such as a customary means in the art to solve the redetermined technical problem, or a technical means disclosed in a textbook or reference book to solve the redetermined technical problem.”

② Typical wording in an office action

Reference 1 discloses XXXXXX. Claim X is distinguished from reference 1 by the technical feature XXXXXX. However, the distinguishing technical feature is common knowledge in the art because XXXXXX. Therefore, claim X does not possess inventive step over the combination of reference 1 and common knowledge.

③ Suggested approach to be used in a response

The difference from the suggested approach to be used in a response mentioned above is that the applicant cannot rebut the examiner on the grounds of the function of the distinguishing technical feature but from these standpoints: (i) reference 1 does not disclose the technical features of claim X identified by the examiner and (ii) the distinguishing technical feature is not common knowledge.

Step 1

Step 1: Does reference 1 disclose all the technical features of claim X except the distinguishing technical feature?

Step 2: Is the technical feature asserted by the examiner as being common knowledge one of the inventive characteristics of the claimed invention?

When a technical feature is asserted by the examiner as being common knowledge, it is better to refute the examiner on the basis of technical effects produced by the feature. Despite the fact that a technical feature asserted by the examiner as being common knowledge is truly an inventive characteristic of the claimed invention, the applicant has to prepare himself for rejection if no amendments, but merely arguments against the examiner’s assertion, are submitted. Applications rejected for that reason account for a large proportion of the applications that our firm has handled.

As it is unusual for applicants to choose to refute the examiner’s assertion that a technical feature is common knowledge, as well as for some other reasons, the author hitherto has dealt with only one application that has succeeded in refuting the examiner’s assertion. Here are the extracts from the office action and our observations.

The examiner commented as below:

“Claim 1 is distinguished from reference 1 by the features that a globally unique packet identifier is included in the UDP multicast request packet, an identifier cache is searched for the packet identifier, and the packet identifier is recorded in the identifier cache.

To make a packet distinguishable from other ones, a globally unique packet identifier is generally included in the packet. Likewise, a globally unique packet identifier can be included in UDP multicast request packets to make the received packets distinct from each other. In order to determine whether or not a packet has been received, a determination is made as to where or not its identifier has been recorded in an identifier list. A cache, a common fast storage buffer in computers, is able to store an identifier list. After a packet is transmitted by a network apparatus, the network apparatus usually makes a record of the identifier of the packet. Similarly, a multicast repeater can make a record of the transmission of a packet after completing the transmission. Therefore, it is obvious for a person skilled in the art to reach the technical solution of claim 1 by combining reference 1 with common knowledge in the art.”

We argued as follows:

“The applicant disagrees with the examiner because:

1. there is no proof that the distinguishing technical features are common knowledge of a person skilled in the art;

2. by recording, extracting and searching for a globally unique packet identifier, the distinguishing technical features are distinct from the technical means making use of the “transmitted” value in reference 1; and

3. in addition to the effect also achieved by reference 1, i.e. enabling the determination of whether or not a packet has been transmitted, the distinguishing technical features of the present invention can further: (1) make it possible to determine, at the time of receipt of a response packet, whether or not a request packet corresponding to the response packet has been transmitted; and (2) make it possible to identify a network address of an originating host and a port associated with an originating application.

The applicant therefore believes that claim 1 is inventive.”

II. Article 26.3 (sufficient disclosure of the invention by the description)

1. Relevant stipulation

Article 26.3 stipulates that the description shall set forth the invention or utility model in a manner sufficiently clear and complete so as to enable a person skilled in the relevant field of technology to carry it out.

As stipulated in

part II of the Guidelines, especially chapter 2 section 2.1.3, the requirement that the description shall enable a person skilled in the art to carry out the invention or utility model means that the person skilled in the art can, when following the contents of the description, carry out the technical solution of the invention or utility model, solve the technical problem, and achieve the expected technical effects.

2. Typical wording in an office action

The description discloses technical solution XXXXXX comprising feature A. But no embodiments of feature A can be found in the description. Hence, a person skilled in the art cannot carry out the invention on the basis of the description. The description does not disclose the invention sufficiently clearly and completely, and consequently a person skilled in the art cannot carry out the invention. Therefore, the description violates Article 26.3.

3. Suggested approach to be used in a response

In the view of the author, a description fulfills the sufficient disclosure requirement as long as a complete technical solution comes into being in the mind of a person skilled in the art after he reads the description, and subsequently he is able to solve at least one of the technical problems to be solved by the invention and produce the anticipated technical effects.

Amendments to the application document are not suitable for eliminating the defect of insufficient disclosure because they are apt to go beyond the scope of the original disclosure and thus violate Article 33. A practical measure is to provide an explanation to the examiner and furnish evidence when necessary. See the chart below for details.

Step 1

Step 1: Is feature A, which is thought of by the examiner as insufficiently disclosed in the description, a necessary part of the claim?

Step 2: Can a person skilled in the art know how to carry out feature A on the basis of the description?

If the answer to step 2 is negative, the applicant has no choice but to demonstrate that feature A actually falls within the prior art. Then cost of this measure is that the applicant can no longer argue for novelty and inventive step by virtue of feature A.

Evidence proving feature A to be a prior art means is preferably in the form of an official publication with a publication date that is earlier than the filing date of the application being examined. When evidence of that kind is unavailable, the applicant can respond by describing at least one embodiment of feature A. The latter response, however, is likely to be unacceptable to the examiner.

4. Incorporation by reference

The applicant sometimes shortens the length of the description by using a reference to other documents. In some cases, those references to other documents are vital in determining whether or not the description sufficiently discloses the invention.

Such references are not considered by the examiner if:

① the applicant cites a document but fails to indicate its name, source, publication date, etc., or the applicant mentions a document and some contents but what is disclosed in that document is irrelevant to the invention or those cited contents are absent from that document;

② the cited document is a non-patent document or a foreign patent document, with a publication date that is not earlier than the filing date of the application; and

③ the cited document is a Chinese patent document with a publication date that is later than the publication date of the application or has not been published up to the publication date of the application.

A qualified citation is considered by the examiner as being an integral part of the description. However, when the examiner finds it hard to match the teaching of a citation, though qualified, with the disclosures in the description (e.g. the cited document discloses a “weighted average method” that is only applicable to white correction, while the invention relates to color correction), then the defect of insufficient disclosure cannot be overcome by the citation.

III. Article 26.4 (the claims shall be supported by the description, and be clear and concise)

Current Article 26.4 is a simple combination of the previous Rule 20.1 (which requires the claims to be concise and clear) and the previous Article 26.4 (which requires the claims be supported by the description). Before the third amendments to the Chinese Patent Law and its Implementing Regulations, objections under the previous Article 26.4 and Rule 20.1 made up the majority of all objections. That is the reason why the number of objections under the prevailing Article 26.4 has seemingly increased sharply since the new law came into effect.

Article 26.4 appears to be one clause, but it actually consists of three independent requirements: the claims shall be supported by the description, the claims shall be clear and the claims shall be concise. Thus, the discussion on the typical wording of the examiner’s opinions and on suggested approaches to be used in a response will be made in three separate sections.

1. Relevant stipulation

Article 26.4 stipulates that the claims shall be supported by the description and shall define the extent of the patent protection sought for in a clear and concise manner.

As stipulated in

part II of the Guidelines, especially chapter 2 section 3.2.1, the requirement that “the claims shall be supported by the description” means that the technical solution for which protection is sought in each of the claims shall be a solution that a person skilled in the art can reach directly or by generalization from the contents sufficiently disclosed in the description, and shall not go beyond the scope of the contents disclosed in the description.

As stipulated in

part II of the Guidelines, especially chapter 2 section 3.2.2, the requirement that the claims shall be clear means, on the one hand, that individual claims shall be clear, and on the other hand, that the claims as a whole also shall be clear; i.e. that first, the category of the claims shall be clear; second, the extent of protection as defined by each claim shall be clear; finally, the claims as a whole shall be clear, which means that the dependencies between the claims shall be clear.

As stipulated in

part II of the Guidelines, especially chapter 2 section 3.2.3, the requirement that the claims shall be concise means, on the one hand, that individual claims shall be concise, and on the other hand, that the claims as a whole shall be concise.

The claims shall be supported by the description.

What claims are deemed not be supported by the description? In practice, they can be classified into two categories: (i) a feature in a claim is described differently in the description; (ii) a claim is formed by unreasonably generalizing the contents disclosed in the description.

What claim is deemed to be a result of unreasonable generalization? In practice, when the technical solution of a claim has one of following problems, the generalization is considered unreasonable:

(a) a person skilled in the art finds it impossible to carry out the technical solution by conventional analytical or experimental means on the basis of the embodiments sufficiently disclosed in the description and the other disclosures in the description;

(b) the technical solution cannot solve the technical problem to be solved by the invention;

(c) the technical solution cannot produce the expected technical effects, or it is hard to determine what technical effects can be achieved by the technical solution.

Problem (a) rarely occurs in electronics applications, so the following discussion relates to objections caused by defects (i), (b) and (c).

2. Typical wording in an office action

Type (i)

Te technical feature in the description that corresponds to feature A of claim X is feature B. That is, the feature described in claim X is not identical to that described in the description. Hence, claim X is not supported by the description.

Type (b)

Feature A of claim X covers a relatively broad scope of protection when compared with embodiment B in the description. It is difficult for a person skilled in the art to foresee that all other embodiments of feature A are able to solve the technical problem to be solved by the invention. Thus, claim X is not supported by the description.

Type (c)

Feature A of claim X encompasses not only feature B, which is described in the description, but also feature C that is not described in the description. Compared with feature B, feature A is so general as to evidently encompass the applicant’s conjectures, the effects of which are hard to predict in advance. Claim X is so general as to lack support in the description.

3. Suggested approach to be used in a response

Approach (i)

When the applicant receives an objection of type (i), the first step is to decide whether or not the inconsistency exists. If there is no inconsistency as asserted by the examiner, then the applicant only needs to explain this. If there does exist an inconsistency, then the applicant usually has to amend claim X so that it is consistent with the description. If the applicant would rather not make an amendment, then it is feasible to argue from the standpoint that feature B is an obvious variant of feature A and thus a person skilled in the art can predict feature B from feature A. The examiner, however, is unlikely to accept this argument.

Approaches (b) and (c)

When the applicant receives an objection of type (b) or (c), the first step is to decide whether or not the technical solution can solve the technical problem to be solved by the invention, whether or not it can produce the expected technical effect, or whether or not it is hard to predict its technical effects. If the answers are positive, then the applicant can respond to the examiner by explaining how the technical solution solves the technical problem and achieves the expected technical effects. If the answer is negative, the applicant may have to amend claim X.

4. Functional features

There is another problem involved in the determination of whether or not a claim is supported by the description, that is, when a claim contains functional features.

In China, functional features are allowed to be included in a claim, but claims merely defined by functional features are impermissible. Since China does not have a standard similar to the USPTO’s “three-prong” test, i.e. an explicit method to determine whether or not features of a claim are functional, it is not rare to see the applicant, the SIPO and the Courts differing with each other in whether or not a feature is a functional feature. During substantive examination, if the examiner finds a feature that is characterized by some function, then he will probably consider it to be a functional feature.

Like the JPO, the SIPO interprets a functional feature as covering all the means that are capable of fulfilling that function. Whether or not a functional feature is allowable depends on whether it is supported by the description. As stipulated in part II of the

Guidelines, especially chapter 2 section 3.2.1, if the function of a functional feature is carried out in a particular way described in the embodiments in the description, and a person skilled in the art would not appreciate that the function could be carried out by other alternative means not described in the description (condition (i)), or a person skilled in the art can reasonably doubt that one or more means embraced by the functional feature cannot solve the technical problem to solved the invention and achieve the same technical effect (condition (ii)), then the functional feature is deemed not to be supported by the description.

In brief, in order to ensure the support of a functional feature by the description, two conditions must be satisfied. First, a person skilled in the art must be aware of other ways able to carry out the function in addition to those described in the description. Second, all the means capable of performing that function can solve the technical problem intended to be solved by the invention.

Suggested approach to be used in a response to objections on the grounds of condition (i)

To contest the examiner’s objection to a functional feature on the grounds that it meets condition (i), the key is to find means capable of fulfilling the function other than the means described in the description. A simple way to get new means is to transform every part of the means described in the description. The more alternative means that the applicant enumerates, the more likely it is that the examiner will accept the rebuttal.

If the applicant cannot find alternative means, then the functional feature may have to be further narrowed structurally or in terms of steps. For the limitation imposed by Article 33, the applicant ultimately probably has to narrow it to the means described in the description and can not meet the examiner halfway by generalizing the means described in the description. For that reason, it is recommended to write multiple claims that become progressively narrower with the inclusion of more restrictions.

Suggested approach to be used in a response to objections on the grounds of condition (ii)

When the examiner disallows a functional feature on the grounds of condition (ii), the applicant should first determine whether all possible means that can perform that function are able to solve the technical problem of the invention. If so, an explanation to the examiner suffices.

If the answer is negative, the applicant needs to identify what function is required for the solution of the technical problem, and revises the functional feature into a feature of the re-identified function. The new functional feature, although also a result of amendments, does not relate to specific structures or steps.

The claims shall be clear.

Lack of clarity of claims lies primarily in: (i) type, (ii) scope of protection, or (iii) dependencies.

Problems (i) and (iii) are infrequent and are dealt with in different ways in different countries. How is problem (ii) addressed in China?

In order for a person skilled in the art to determine the boundaries of the scope of protection of an invention only in the light of the claims, the SIPO generally requires the scope of protection of a claim be clearly determined without taking the description into consideration. For that reason, if the examiner thinks the scope of protection of a claim is unclear, the applicant should first judge whether the claim is clear enough even without referring to the description.

If the claim by itself is unable to provide a clear definition of the scope of protection, then it usually needs to be amended on the basis of the description.

Amending a claim inevitably incurs the risk that the amendments go beyond the scope of the original disclosure. How can we achieve a clear claim without causing the amendments to go beyond the scope? Compared with the defect of amendments going beyond the scope that is absolutely prohibited, lack of clarity sometimes is allowable if accompanied by adequate explanations. Thus, if we notice that amendments capable of completely resolving a lack of clarity may go beyond the scope of the original disclosure, we make as many amendments as the scope of the original disclosure permits and remedy the remaining lack of clarity through explanations. If we decide to do that, we usually make a phone call to the examiner to discuss the acceptability of that measure. Since the examiner also intends to conclude the prosecution at an early date, and the applicant is subject to prosecution history estoppel (that is, explanations also limit the scope of the claim), we often succeed in overcoming a lack of clarity by means of amendments plus explanations or mere explanations.

The claims shall be concise.

Claims are deemed not to be concise in cases where (i) identical features are present in two (or more) claims one of which is dependent on the other, or (ii) there are several claims covering the same protection scope.

No complicated response is needed if the applicant receives an objection on the grounds of redundancy of claims. The first thing to do is to determine whether the features pointed out by the examiner are identical with each other or whether those claims have the same protection scope. If not, explain to the examiner. If so, delete the features in the later claim, or delete all but one of the claims.

In view of the means-plus-function limitation in the US, some applicants prepare two claims that differ from each other only in that the components in one of them are named “XXX unit/section” and those in the other are named “XXX means”. Such two claims cover essentially the same protection scope. Thus, if they are found by a SIPO examiner during substantive examination, the examiner requires that one of them be deleted.

IV. Article 31.1 (unity)

1. Relevant stipulation

Article 31.1 stipulates that an application for a patent for invention or utility model shall be limited to one invention or utility model; two or more inventions or utility models belonging to a single general inventive concept may be filed as one application.

Rule 34 stipulates that two or more inventions or utility models belonging to a single general inventive concept which may be filed as one application in accordance with the provisions of Article 31.1 of the Patent Law shall be technically inter-related and contain one or more of the same or corresponding special technical features; the expression “special technical features” shall mean those technical features that define a contribution which each of those inventions or utility models, considered as a whole, makes over the prior art.

2. Typical wording in an office action

Claims 1 and X do not share the same, or corresponding, technical features, so they do not share the same, or corresponding, special technical features (or claims 1 and X share the same, or corresponding, technical features A and B, but features A and B are common technical means in the art/are disclosed by reference C). Claims 1 and X do not belong to a single general inventive concept, thus violating Article 31.1.

3. Suggested approach to be used in a response

The SIPO adopts the same standard as the JPO in determining the presence or absence of unity between claims, i.e. whether they share the same or corresponding special technical features. As stated in the law, “special technical features” means those technical features that make a contribution over the prior art. In other words, a special technical feature distinguishes the invention from the prior art.

Corresponding special technical features may be special technical features that enable two inventions to match each other and solve technical problems associated with each other. For instance, “3-pin plug” and “3-hole socket” are corresponding special technical feature if they both are special technical features. Corresponding special technical features may also be technical features that can replace each other, solve the same technical problem and make the same contribution over the prior art. For instance, “rubber cushion” and “spring” are corresponding special technical features if they can replace each other and make the same contribution over the prior art in respect of elasticity and vibration damping.

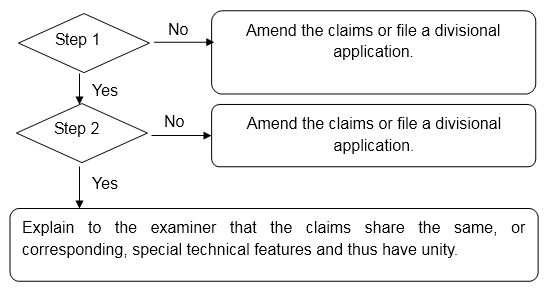

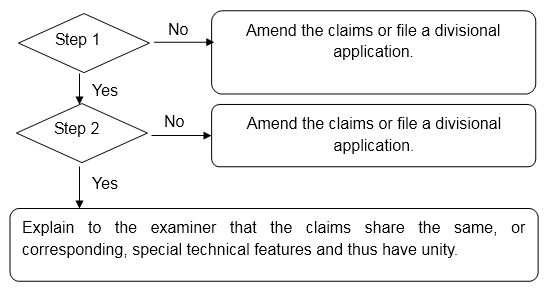

Thus, when the applicant receives an objection on the grounds of lack of unity, the following approach can be considered:

Step 1

Step 1: Do the claims share the same, or corresponding, technical features?

Step 2: Are the same, or corresponding, technical features special technical features?

If the examiner has commented on claim 1 and its dependent claims, it is inappropriate to delete claim 1 and its dependent claims while retaining claim X (which the examiner thinks has no unity with claim 1 and on which the examine makes no comment) and its dependent claims because the examiner will consider such amendments not to be in compliance with Rule 51.3 and reject the application in accordance with Article 31.1 on the basis of the application document without including those amendments.

V. Article 33 (the amendments shall not go beyond the scope of the disclosure in the original application document) & Rule 43.1 (the divisional application shall not go beyond the scope of disclosure in the initial application)

1. Relevant stipulation

Article 33 stipulates that an applicant may amend his or its application for a patent, but the amendment to the application for a patent for invention or utility model may not go beyond the scope of disclosure contained in the initial description and claims.

Rule 43.1 stipulates that a divisional application filed in accordance with the provisions of Rule 42 shall be entitled to the filing date and, if priority is claimed, the priority date of the initial application, provided that the divisional application does not go beyond the scope of disclosure contained in the initial application.

As stipulated in

part II of the Guidelines, especially chapter 8 section 5.2.1.1, the scope of disclosure contained in the initial description and claims includes the contents described in the initial description and claims, and the contents determined directly and unambiguously according to the contents described in the initial description and claims, and the drawings of the description.

2. Suggested approach to be used in a response

Although Article 33 and Rule 43.1 are directed to different things—amendments and divisional applications, they are the same in essence—the restriction imposed by the scope of disclosure contained in the initial description and claims. That is the reason why the two clauses are discussed together here.

The above discussion about Article 26.4 mentions “the contents disclosed in the description”. Are there any differences between “the contents disclosed in the description” and “the disclosure contained in the description”? According to the

Guidelines, “the contents disclosed in the description” consist of “the disclosure contained in the description” and “the contents reached by generalization from the disclosure contained in the description”, and “the disclosure contained in the description” consist of “the contents described in the description” and the contents determined directly and unambiguously from the contents described in the description and from the drawings”. In other words, legally speaking, the standard for determining whether a claim is supported by the description is less stringent than that for determining whether an amended claim is within the scope of disclosure in the initial description, that is, even if an amended claim is though to be supported by the description, it may be considered to be beyond the scope of disclosure contained in the initial description.

What is “the scope of disclosure contained in the initial application document”? The

Guidelines seem to give an explicit stipulation, but fail to reveal what “determined directly and unambiguously” means. According to our experiences, “the contents determined directly and unambiguously” generally refer to those contents that are not described in the initial application document but are the

sole results of determination by a person skilled in the art from the contents described in the initial application document and from the drawings.

It is thought that some SIPO examiners narrowly construe what is meant by “the sole results” in the following way: Suppose that what is described in the initial application is A while the amendment is B. B is considered to be determined directly and unambiguously from A only if A can be deduced from B and B can also be deduced from A.

As an example, the amendment is that “said second lid is shaped to offer an incision” whereas the initial description describes that either the upper or the lower section of the second lid is shaped to offer an incision. Those examiners might think that although the amendment can be deduced from the initial description (that is, B can be deduced from A), but it additionally encompasses a circumstance in which the middle section of the lid is shaped to offer an incision (that is, A cannot be deduced from B), and as a consequence the amendment goes beyond the scope of the original disclosure.

Because of the examiner’s rigidity in the interpretation of “determined directly and unambiguously”, when we amend the application document, we can only use the exact wording found in the initial description and claims.

Fortunately, some examiners from the SIPO, including those from the Patent Reexamination Board, do not interpret “the sole result” in the same way. They are more concerned about whether an amendment can be deduced from the initial application document (that is, whether B can be deduced from A) and do not require A be deduced from B. That can be demonstrated by the fact that the Patent Reexamination Board affirmed the amendment in the above example as not being beyond the scope of the original disclosure.

To sum up, when the examiner raises an objection on the grounds that the amendment goes beyond the scope of the original disclosure, the applicant should first determine whether further amendments can eliminate the defect without considerably narrowing the scope of protection. If so, such further amendments are preferred. If the applicant thinks that such further amendments would unduly narrow the scope of protection and the examiner is excessively strict in holding that view, the applicant can argue strongly and even submit a request for reexamination.

VI. Rule 20.2 (the independent claim shall include all the essential technical features)

1. Relevant stipulation

Rule 20.2 stipulates that the independent claim shall outline the technical solution of an invention or utility model and state the essential technical features necessary for the solution of its technical problem.

As stipulated in

part II of the Guidelines, especially chapter 2 section 3.2.1, “essential technical features” refer to the technical features of an invention or utility model that are indispensable in solving the technical problem and the aggregation of which is sufficient to constitute the technical solution of the invention or utility model and distinguishes the same over the technical solutions described under the heading “Background Art”.

2. Typical wording in an office action

The present invention is intended to solve the technical problem …. It is known from the description that feature A is indispensable to the solution of that technical problem. Claim X lacks feature A, so it does not comply with Rule 20.2.

3. Suggested approach to be used in a response

The chart below illustrates how the applicant can respond to the examiner.

Step 1

Step 1: Can claim X solve

at least one (not “all”) of the technical problems intended to be solved by the invention?

Step 2: Is feature A indispensable to claim X?

If it is found that claim X lacks not only feature A but also other features, the applicant can consider adding feature A to claim X and using the other features to form claims dependent on claim X, instead of adding all the features to claim X. This way, the applicant will not only obtain a relatively broad scope of protection, but may also avoid being defeated by someone who attempts to invalidate claim X on the grounds that it lacks essential technical features, by subsequently incorporating those dependent claims into claim X.

VII. Inventions Concerning Computer Programs

Inventions concerning computer programs are peculiar to the field of electronics. The

Guidelines stipulate in detail in chapter 9 of part II how to examine an invention concerning computer programs. There is an important requirement for inventions relating solely to the flow of steps in a computer program: the apparatus claim shall be drafted in such a way as to completely correspond to the process claim reflecting the flow of steps in the computer program. “Completely correspond to” means that the subject matter title of the apparatus claim corresponds to that of the process claim, each component in the apparatus claim corresponds to each step in the process claim and the respective components operate in the same chronological order that the respective steps are conducted.

When the examiner notices that the apparatus and process claims of an invention relating only to the flow of steps in a computer program do not completely correspond to each other, he usually raises an objection to the product claim on the grounds of violation of Article 26.4 if the non-correspondence does not result from an amendment, and raises an objection under Article 33 if the defect is caused by an amendment. The typical wording of the two kinds of objections is as follows:

Objection in accordance with Article 26.4

Claim X comprises physical components and functional modules. The functional modules protect a control method of the present invention carried out by a computer program—rather than physical components carrying out the control method. Thus, claim X fails to clearly show whether what is claimed is a product or a method, so it violates Article 26.4.

Objection in accordance with Article 33

“XX unit” is added to claim X. No XX unit is mentioned in the original application document, and it is the CPU/controller that fulfills the function of XX unit. Therefore, the amendment to claim X goes beyond the scope of disclosure contained in the original application document, thereby violating Article 33.

The above typical wording is by no means exhaustive, and the examiner’s objections are in various forms. Thus, if the examiner issues an objection to the product claim the invention of which relates only to the flow of steps in a computer program, it would be best for the applicant himself (or via his agent) to discuss this with the examiner in order to find out whether the examiner wants the applicant to amend the product claim so that it completely corresponds to the process claim. If the answer if positive, it is appropriate to amend the product claim, because arguments will be of no avail, and such amendments do not unduly affect the scope of protection and are unlikely to be considered to go beyond the scope of the original disclosure.

Part III. Conclusions

Owing to his relatively limited experience, the author cannot claim that the above is anything more than a brief and incomplete summary of common objections raised by the SIPO examiners in office actions. However, he hopes that it will be of help to the reader and welcomes any comments.